It all starts with a ping in chat. The boss drops a video meeting link into the team channel for a “quick convo” about annual planning, which is neither quick nor just a convo. You scramble to pull together some data and slides, because you realize your colleague who was doing some opportunity research is out today. “Nevermind,” the boss says, “let’s just get aligned with whoever is available.”

Hours later, after much frustration and flinging ideas at the wall, the boss decides on a plan that no one really wants to rally around, but the boss is the boss. What happened to alignment? You find yourself wondering: was this the best outcome, and could there have been a better way to get there?

If this situation sounds familiar, you are certainly not alone. In fact, I have spoken to hundreds of workers across roles and industries and they all share the same frustration that too often important decisions are happening ad hoc in meetings or Slack, leading to poor results.

So, what are we doing wrong?

Cleaning up our bad decision making hygiene

Extensive research shows that running an entire decision making process synchronously introduces many bad practices that worsen decision outcomes:

- Lack of ownership: Without an established decision owner, it is unclear who should be driving the process.

- Lack of information: When you attempt to make a decision during an impromptu meeting, there is often not enough time to source the best options and collect the relevant data.

- Introduction of groupthink: Often, dissenting views are minimized in order to maintain social harmony, which can prevent diverse ideas.

- The “loudest voice” effect: Not everyone is comfortable speaking up during meetings, especially when leadership is in the room. So it’s common that the loudest voice, not necessarily the smartest, wins.

Obviously, some decisions that come up during a meeting (where should we go for lunch after this meeting?) can be settled right then and there. However, most important decisions benefit from a decision making process.

Now, don’t let the word “process” sound like a scary monster that’s going to add something big and cumbersome to your day. It’s actually quite easy to improve decision making within your organization in just a few easy steps. I promise.

Get everyone on the same page

The first things to consider when beginning the decision making process is reducing ambiguity around the decision being made, understanding the scope of the decision, and identifying whether it is a one-way or two-way door decision.

One-way door decisions are like exiting airport security: they are nearly impossible to reverse and require a lot of time. Whereas two-way door decisions can be reversed if the results are suboptimal, like a change to your product’s pricing and packaging.

One of the biggest proponents of one-way and two-way door decisions is Richard Branson, who realized that most business decisions are actually two-way decisions: decisions where we should feel comfortable moving fast, learning, and iterating.

Once you understand the scope of the decision, bring clarity and alignment to the decision making process by starting with these three steps:

- Identify the specific problem or opportunity

- State your goals

- Give any additional context that’s available

All of this information should be clearly documented and openly accessible to anyone involved in the decision, thus removing the need for alignment meetings that clog calendars. In other words, don’t just throw important info into a Slack channel.

Accountability is key for making decisions and moving forward

Why do decisions linger to the point where we wind up on harried calls rushing an outcome? It’s because we often fail to set up systems of accountability to drive decisions forward.

After establishing the scope of the decision to be made, the next step is to define the following:

- The decider: This is the person who is in charge of making the final decision, as well as the person responsible for keeping everyone moving forward. The decider for most non-business critical decisions should be someone who is close to the relevant data, as leaving all decisions up to leadership can result in slower, more error prone decisions.

- The contributors: Contributors should be stakeholders who are close to the data around the decision being made. Contributors are empowered with providing options and information to back those options, as well as opinions when weighing-in on the best path forward.

- The due date: Key to the decision making process is identifying a due date. A due date too soon means there may not be enough time to gather enough information, but a due date too far into the future might impact our ability to implement the decision, learn, and iterate. Choose a due date that makes sense for the scope of the decision and hold everyone to it.

By establishing the decider, contributors, and due date, everyone can now operate asynchronously within the allotted time frame to focus on their roles. The DACI framework is a great way to establish processes and assign key contributors in order to help make decisions.

Weigh-in on options without bias

One of the biggest problems with making decisions in meetings is that meetings perpetuate groupthink and the introduction of many biases. By driving the decision making process asynchronously we can remove many biases by giving people the time and space to consider the options, as well as a level the playing field for providing responses.

With the various options documented, allow the contributors and decision maker to weigh-in on the positives and negatives. No peeking!

Might it be slightly awkward to find out you and your boss have dissenting opinions? Maybe. Is it worth a better outcome? Definitely.

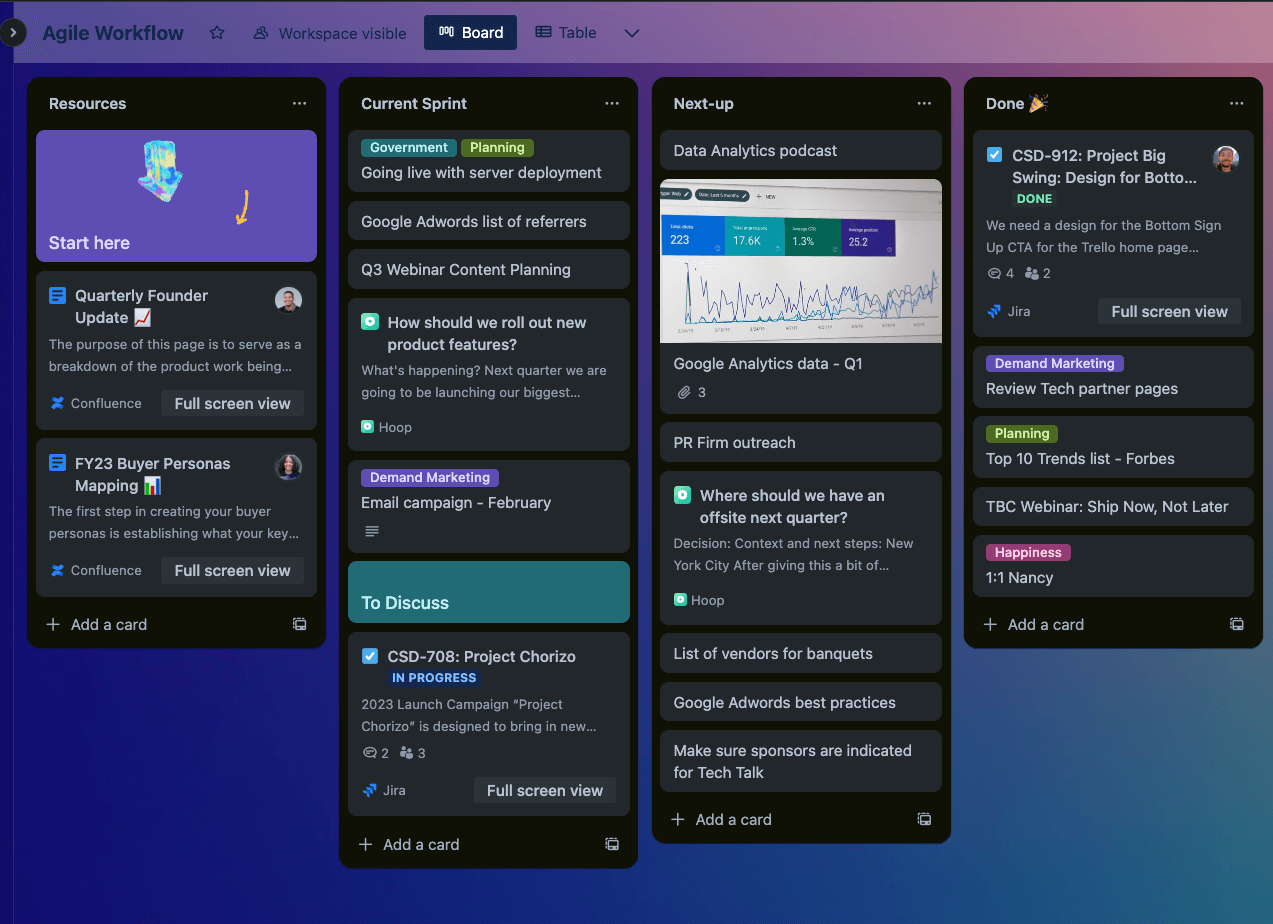

Attach Hoop decisions to your Trello board using smartlinks.

Depending on the tool you are using to document your decision this can be done in a few different ways – every contributor gets their own card to respond in Trello, collapsible fields in Confluence for each contributor, or an app like Hoop which is built for asynchronous decision making.

Sometimes it might be necessary to hop into a meeting if the weigh-in process reveals a serious lack of alignment. In these cases, at least everyone will be going into that meeting having had the opportunity to openly and honestly share their thoughts beforehand, which will allow for a much more productive and less awkward conversation.

Document and distribute the decision

When the decision has been finalized, document the decisions in an openly accessible source of truth, and broadcast it far and wide. Make sure all stakeholders are aware of the outcome and have a place for them to learn more about the outcome and its implications. Luckily, this can all be done asynchronously without having to organize a meeting:

- Document the decision in an open format like a Confluence page or Hoop

- Record a Loom video explaining the decision and allow for async Q&A

- Establish a source of truth for all company decisions so that anyone can easily find that information in the future

- You may also consider additionally sharing the decision outcome as a song and dance, should the mood suit you.

Four easy steps for better decision making, faster

As you can see, getting out of the Zoom room and into more asynchronous decision making habits can not only help us make better decisions but also free up our calendars for the important deep work that fuels our days.

Remember that scenario we described earlier? All of that stress, distraction, and wasted time can be erased and replaced with more important work, like funny cat TikToks for the company blog (serious ROI driver.)

To recap, here are the four steps to implement an asynchronous decision making process today:

- Clarify the scope of the decision

- Create accountability

- Weigh-in without bias

- Document outcomes and distribute

The key is to remember that most decisions are two-way doors that don’t require us to have 100% of the information in order to move forward. At the end of the day, we should be focused on establishing a process that allows us to continually decide, implement, learn, and iterate.

)

)